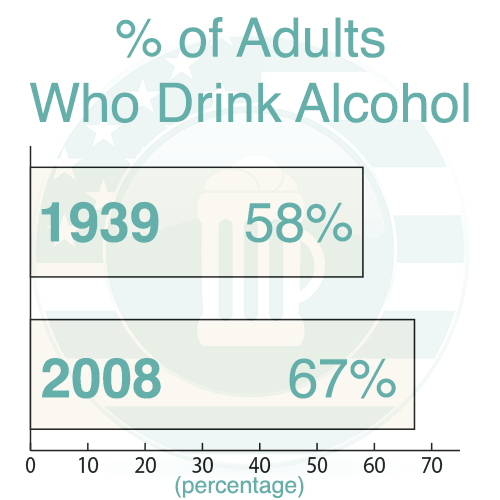

Alcohol use rates haven’t shifted drastically in the United States over the past several decades. In 1939, for example, 58 percent of American adults admitted to Gallup pollsters that they drank alcohol. In 2008, that survey was repeated, and 67 percent of American adults admitted to drinking alcohol.[1]

It seems to suggest that alcohol and America are somehow inexorably linked. People in this country like to drink, no matter what time period they might be living in.

In some ways, alcohol is the perfect drink for America, as its persistence can be tied to politics, money, and entrepreneurship. Unfortunately, alcohol use in this country can also be tied to illness, despair, and social ills. Understanding why people drink in this country, and why they have drunk in the past, could be the key to help people avoid such drinking patterns and such negative outcomes in the future.

Alcohol and the Start of the Country

When the explorers first came to the shores of the United States, they encountered a group of native people that had little use for alcohol.[2] Some tribes produced a form of beer for ceremonial purposes, but some tribes had no concept of alcohol at all. Very few of these native people imbibed alcohol for recreational purposes. It just wasn’t something that was done.

For European travelers, however, alcohol was a part of the culture they had left behind. These people likely grew up drinking alcohol with most meals, and they clearly valued alcohol as a commodity, as they used it as a bartering tool with the native population.[3]

Once communities were developed and families began to settle down, many planted crops they intended to develop for alcohol production purposes. Thomas Jefferson, for example, planted 24 different wine varieties on his Monticello grounds in 1807, and he thought the act would raise the stature of the new country he was so committed to.[4] He wrote:

“… We could, in the United States, make as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe, not exactly the same kinds but doubtless as good.”

For scrappy colonists, making drinks that were as good as those they got back home could give them a sort of honor and place they’d been craving. In addition, alcoholic drinks served another important purpose for early residents of this country. Prior to the late 1800s, it was difficult to keep drinks cold. There were no refrigeration units available, and ice wasn’t always either clean or nearby. Most drinks were kept at room temperature, and they hadn’t been pasteurized or otherwise decontaminated. People who drank these beverages often got sick, and they couldn’t tell which drinks were healthy and which were not.[5]

Alcoholic drinks were a boon because the alcohol content worked as a preservative. Colonists without access to refrigeration could process fruits and berries into drinks they could take in later, without worry that they would fall ill. For them, the drinks seemed healthy.

Prohibition Dampers Enthusiasm

In the late 1800s, however, American love for alcohol began to wane as saloon culture began to rise. The Anti-Saloon League, formed in 1893, suggested that drink was the cause of all sorts of societal ills, and in time, local laws banning drink began to spring to life.[6] By 1919, it had been banned altogether. The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution specifically prohibited the manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcohol. It’s only 111 words long, but it had a deep impact.[7]

The law reduced the number of people who drank; however, within a few years of enactment, levels of drinking had almost reached pre-Prohibition levels.[8]

What were these people drinking? Research suggests that they were drinking beverages they’d made at home. Businesses helped to boost these home brewers. Eight years after Prohibition was enacted:

- Five hundred malt and hop shops operated in New York City alone.

- About 100,000 stores nationwide sold malt syrup that could be used for beer.

- Approximately 25,000 shops sold home-brewing equipment.

- Magazine writers were posting articles about how many homemakers were making their own beer.[9]

Clearly, the law wasn’t keeping people away from drinking.

A Rising Awareness

By the late 1930s, alcohol was once again legal for adult consumption in the United States. Researchers knew that banning the substance didn’t make people stop drinking, but they wondered if pointing out the physical harm that alcohol could cause might make people slow down or stop their intake.

Researchers at the Yale University Laboratory of Applied Physiology and Biodynamics began researching the link between poor health and alcohol consumption, and in 1940, the first edition of the Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol was founded.[10] Consumers now started to learn that alcohol wasn’t just an ill that could impact a society. They were learning that drinking could impact health and longevity.

At the same time, a group of people who had started to experience their own troubles due to drink began to come together in informal meetings in which they discussed alcohol and the difficulties it can cause. In 1939, the work of that group culminated in the publication of a textbook, Alcoholics Anonymous, which is still in use today.[11]

These years are vital to the understanding of the history of alcohol in America as they contain the acknowledgement of the physical ills of drink and the nascent ideas of the recovery movement. But, drinking didn’t end in the 1940s. There was still a lot of pressure to both make and consume alcohol.

A Money-Making Venture?

Even while AA grew, entrepreneurs were pulling together plans to boost production of alcoholic beverages within the borders of the United States. For these businessmen, alcohol had the potential to make them a lot of money. One such man, speaking to Fortune magazine in 1934, had this to say:

“There is no reason why our industry should be a small industry. It ought to be – it can be – bigger than the automobile industry, bigger than the steel industry, if wine makers will seize the opportunity that lies before them.”[12]

For this businessman, wine represented a healthful drink, not a hard booze. If he could just market the drink differently, he figured, he could make a ton of money. Others seemed to feel the same way.

Small wineries sprang up all across the country, and in the 1950s, the Kennedys entering the White House – a young couple with an affinity for all things French – helped to boost the drinking mood. People wanted to be like Jackie, and if that meant drinking wine, they would do so.[13]

The ability to know wine terms, and to describe what a wine tasted like, became a new hobby for Americans. And that same connoisseur mentality spread into other alcohol types, including beer and spirits. That ethos exists today.

Alcohol in Modern Times

Now, Americans are about evenly divided, when it comes to liquor choices.[14]

The marketing push, in which distributors suggested that wine was healthful and cultural, seems to have made wine a very popular drink. Even so, many people in the United States don’t seem to drink wine in a healthful manner.

In fact, no matter what people are drinking, many of them tend to be drinking to excess. For example, a 2010 poll suggests that alcohol dependence prevalence stands at 4.7 percent in the United States.[15]

The Future

Alcohol has long been a part of the fabric of this country. If the culture continues to associate drinking with good taste, business sense, and success, it’s unlikely that these numbers will go down, either.

So what can people do to help? It starts with sobriety. The more people who choose to stop drinking destructively, and who share that message far and wide, the more the link between alcohol and success will weaken. Each person who makes that choice can help. If we all do so, we could write a whole new future for America, one that doesn’t include alcoholism.

Citations

[1] Newport, F. (July 30, 2010). “U.S. Drinking Rate Edges Up Slightly to 25-Year High.” Gallup. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[2] Beauvais, F. (1998). “American Indians and Alcohol.” Alcohol Health & Research World. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jones, J. (June 24, 2014). “Thomas Jefferson’s Wine.” Chicago Tribune. Accessed Feb, 20, 2015.

[5] Kransner-Khait, B. (n.d.). “The Impact of Refrigeration.” History Magazine. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[6] “Why Prohibition?” (n.d.). The Ohio State University. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[7] “National Prohibition Act.” (n.d.). Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[8] Miron, J.; Zwiebel, J. (April 1991). “Alcohol Consumption During Prohibition.” National Bureau of Economic Research. Accessed Feb. 20. 2015.

[9] Jabloner, A. (December 1997). “Homebrewing During Prohibition.” Brew Your Own: The How-to-Homebrew Beer Magazine. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[10] “The History of the Center of Alcohol Studies.” (n.d.). Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[11] “Historical Data: The Birth of AA and its Growth in the U.S./Canada.” (n.d.) Alcoholics Anonymous. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[12] “Can Wine Become an American Habit? (Fortune, 1934).” (March 25, 2012). Fortune. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[13] Alig, P. (n.d.). “The Wine Boom in the United States.” NetPlaces. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[14] Jones, J. (Aug. 1, 2013). “U.S. Drinkers Divide Between Beer and Wine as Favorite.” Gallup. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.

[15] “United States of America.” (2014). World Health Organization. Accessed Feb. 20, 2015.